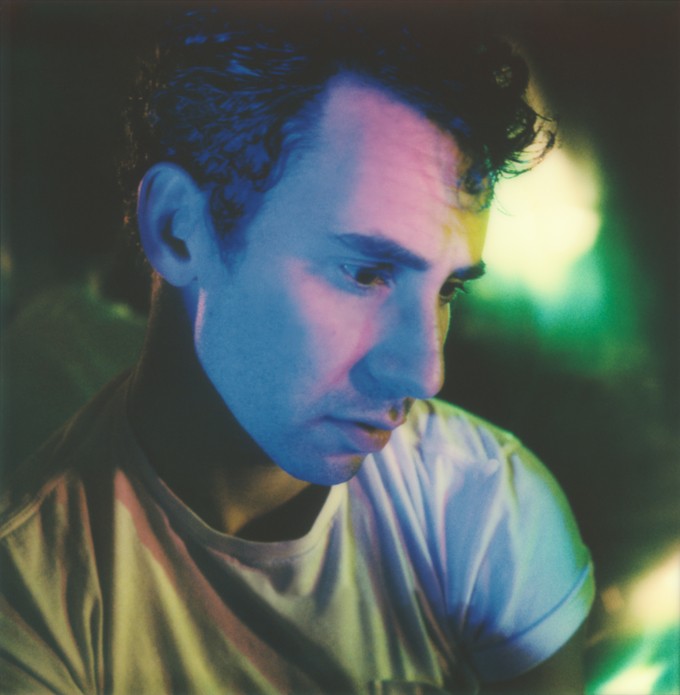

"There's millions of people in the world - you don't want them all to like you, you want to find your people," explained Jack Antonoff earnestly last month to fans at a Q&A event held on the rooftop of New York City's Electric Lady Studios. "That's your goal as an artist," he continued, "My original intention, whether it's a Bleachers record or some big pop record, is just to find its people." Holding court in support of his recently released third album, 'Take The Sadness Out Of Saturday Night', Antonoff cracked jokes and answered heartfelt questions from fans throughout the hour-and-a-half grilling, in between performing acoustic renditions of his songs.

Throughout all his musical endeavours, and most predominantly showcased via his own project, Bleachers, Antonoff has been searching for those like-minded individuals he calls his 'people' - a collective who truly understand and empathise with the feelings of loneliness, grief, and love that drive his songwriting, and it’s particularly with this new album that those feelings are emoted in their purest sense.

Click here to order the new CDM x Bleachers zine (i.e. a mini-magazine featuring photos + quotes from this cover-story).

The ten track album is comprised of five sets of siblings - two songs which look at different sides of the same coin, whether it be 'Secret Life' and 'Big Life' in which the concept of being bored in love is tossed around, or in 'What'd I Do With All This Faith?' and '91' where Antonoff contemplates the past and the future ("Storefronts change a new war on," he sings in the latter, also referencing his previous songs, 'I Miss Those Days' and 'Dream Of Micky Mantle').

If there's one thing you take away from listening to 'Take The Sadness Out Of Saturday Night', it's the understanding that grief is almost an impossible concept to hide away in the back cupboard of your mind's house (during the album cycle for 'Gone Now', Antonoff referred to many of the songs as different rooms within a home), and that there's a power that comes in acknowledging the inevitability that loss plays in each of our lives. It can unite us.

"Ain't no faith can take your placе," sings Antonoff on album-closer, 'What’d I Do With All This Faith?', and similarly, on 'Everybody Lost Somebody' from his last album, he reflected, "I know that I'm lost / Lost in a world without you." In every building-block of the Bleachers universe, stands strong the realisation that there is a way to honour your grief - by choosing to hold pieces of it, and letting them co-exist as part of your identity. "It becomes your identity because you feel like you must make sense of this, so then you hold it, and you almost feel pride about it," he confides.

The flip side of that is what can happen when you hold on too tightly. In discussing ‘TTSOOSN’, Antonoff speaks about a recurring image he sees of himself standing at the doorway to his future, carrying the heavy weight of his life experiences (he asks in ‘How Dare You Want More’, "Who am I without this weight on my shoulder?"), being unable to pass through the doorway to the next chapter without leaving parts of his emotional baggage behind. Though the album may not answer the question, it instead poses a different one: Why can't joy be part of the equation? Why can't we get rid of the dated concept that to have any joy, there has to be all this pain? And for anyone, that joy could come in many forms - but for Antonoff in particular, it's sharing his music with his people, and especially, performing live.

And now, this week, on September 11th, 2021, Bleachers will return to the live stage for the first time in two year - headlining Antonoff's curated hometown music festival Shadow Of The City, that has run since 2015, with musical friends Claud, Blu DeTiger, and more along for the ride. He's filled with euphoria thinking about finally touring ("It's going to be really heavy and wonderful and filled with joy and intensity," he says), and the event will see his people truly united, as they take the sadness out of Saturday night. Together.

We spoke with Jack Antonoff ahead of the release of new album 'Take The Sadness Out Of Saturday Night' about his new body of work, accepting another's sadness, imagery in songwriting, the ownership transfer of his music, and much more...

COUP DE MAIN: You've described tour as waking up somewhere new with no baggage, and you've also explained how utilising your live band in this album was very important. How have you been adjusting, going from a year of no touring, as things start to open up, and people start to be more optimistic about the future of returning to touring?

JACK ANTONOFF: Yeah, it's weird. You know, a few months ago we were like, 'Who knows?' Then we put the tour up, hopefully, and now it's seeming like it's going to happen. It starts in September. I think I'll know how I feel in mid-August because right now it's still far enough away where I'm like, 'Is anything firm?' But this is happening and I'm over the moon. I don't know what's going to happen to me emotionally. It's going to be really heavy and wonderful and filled with joy and intensity. I can't wait. I also can't imagine it at the same time.

CDM: I’ve been listening to 'Take The Sadness Out Of Saturday Night' for the past few days on repeat now, and it’s such a beautiful piece of work. I officially apologise for constantly tweeting at you for the past four years asking where the album is... I'm glad you took your time with it.

JACK: I love it. I feel very supported. I feel encouraged and bullied, but mostly encouraged.

CDM: At what point did the phrase "take the sadness out of Saturday night" first appear? It pops up in a couple of songs.

JACK: I write in two ways. I either just sit down and write, or I get these things in my head. For example, 'Stop Making This Hurt', I've had that line forever. I was like: I want to say "stop making this hurt, say goodbye like you mean it," and it was just batting around. Whereas 'Secret Life', I just sat down and wrote it, and I don't know where the fuck it came from. I love that song. It's all about wanting to build a life that's no one else's, with someone you love. But "take the sadness out of Saturday night" was one of those lines where I had it and I was like: Oh, I really see that line, it harkens back to the way I grew up, but it's also about the future. It's about getting rid of this evil eye, getting rid of this concept that there has to be all this pain to have any joy - and if you have too much joy, then you'll be damned. It just was all connected. It was connected to the feeling like Bleachers is somehow a Saturday night sound - 'Get me the fuck out of here, we've got this one moment to feel ourselves.' So then I wrote it into 'Chinatown' in a very specific way: "Give me that big red light and take the sadness out of Saturday night." It's saying someone else can do it. I'm drawing connections, but when I was finishing, I had nearly all of 'Stop Making This Hurt', and when I was writing the bridge I couldn't figure out how to frame it because the whole song is like, 'Daniel's doing this, Jimmy's doing this, my mom, my dad, everyone's fucking up, stop making this hurt, say goodbye like you mean it, drop all your baggage.' I needed a part that was like, 'Well hold on a sec, it's not that simple.' So then I was like, "If we take this sadness out of Saturday night, I wonder what we'd be left with, anything worth a fight? I run from the darkness, shout the light," this idea of the journey, sort of 'I Wanna Get Better' in a way too, of wanting something, looking for hope, trying to take the sadness out of Saturday night - that's the glory. It's not being better. It's not being fully well and only having joy. It's to be looking up at the sky and say, 'Let's do it. Let's give it the [old] Harvard try.' It's very romantic in 'Chinatown', but the 'Stop Making This Hurt' version of "take the sadness out of Saturday night" is a lot more to the deepest sentiment of how I mean it.

CDM: In '91' you sing, "Storefronts change a new war on," calling back to lyrics in 'I Miss Those Days' ("And everyone is changing / And storefront's rearranging") and 'Dream Of Mickey Mantle' ("Kim’s Video closed and a war goes on and on") from the last Bleachers album. Why is certain imagery like storefronts, and war, such recurring images for you?

JACK: I think they are the perfect example of big and small. You walk down your street, and there are the stores you kind of know; you know the people that work there, and one day they're gone. And no one cares. But it's huge. In your tiny little world it's massive, all of a sudden everything's changed on your block, but nothing's changed. So it's this rolling identity of storefronts that just come and go, and they mean so much, but they mean nothing at all. I think that there's something in connecting that to the idea of something as massive as a war - what could be bigger? They sort of come and go almost like storefronts, where it means everything and nothing. Sometimes you walk through life or your neighbourhood, and you're just like, 'Jesus, so much is shifting, so much is changing, but it's just kind of the way it is.' I like the imagery. I'm often walking around. I write a lot when I walk and am thinking, like, 'Jesus Christ, what the fuck is going on?' And then, immediately, it makes me think, 'Jesus Christ, what the fuck is going on in my life?' And that's how I sort of get to the writing. I just always see myself on the block, walking, and thinking about what used to be here and what's going to be here.

CDM: I always get tripped out looking at old photographs of the same street that you're super familiar with, seeing old photos even from the 80s, it's hard to comprehend that everything was so different then.

JACK: Yeah, and I love objects and things that aren't alive that hold so much meaning. This [home studio] room I'm in is similar, there's so much meaning to it - it's alive, but it's not, and one day it'll get knocked down or something, or be underwater, and the things that come from it may or may not live on but there's a life to it. These things have life that aren't alive.

CDM: You were 7 in 1991 during the Gulf War - do you vividly remember watching the footage of that on TV?

JACK: Yeah, I knew I wanted to open the album with that. That's why I say "black, white, and green," because there was black and white footage, but when there'd be an explosion it would be in green. It must have been night vision or something. Very odd, and I was young, it was my first experience with understanding about a war that was going on - it was a million miles away from where I was in New Jersey, but there was anxiety to it. I remember we would watch it and I just thought, 'This is so dysfunctional.' And so it seemed like a perfect setup to describing some dysfunction in my family going on at that time. It's a little bit poetic, but it's true - I was a kid sitting there watching the Gulf War and also witnessing some disconnects that my mother was having because of things going on in the house. And that's the structure of that song - my mother, my ex, and then my future.

CDM: You have really specific memories that appear in your songwriting, and I was wondering how your memory with your past works? Do you have vivid moments throughout your childhood? Do you find new things come back to you now?

JACK: I'm not sure. They sort of come and go. Certain things are stamped, but the things I know a lot about I don't tend to write about. It's more these passing things, like that memory of watching the Gulf War, all of a sudden it just hit me one day, and I was like, 'Ah, I remember that.' It made me think. I think the memory being blurry is what made me want to write about it. I always sort of feel if you know something very well, you don't tend to write about it because it bores you. But if you have a place in a time, and a feeling, and it's all really heavy and you're not even sure why, then it becomes really important on a personal level to write about it because you want to figure out: 'What the hell is this? Why is this such a heavy memory? Why is sitting there watching the Gulf War - it wasn't about the war - why was that so big to me?' And as I started to realise, it's because it's early memories of recognising a different kind of war, one in the household.

CDM: The lyric, "I'm here but I'm not / just like you I can't leave," is really powerful. Why is the ending of things so hard? Is it that people are so afraid of the unknown and what comes after?

JACK: Anything final... I think humans, in general, are backing up to the next existential crisis of existence; we won't be here forever. So, that's a little big. It's tough to hold that everywhere you go, but it's with us. So if someone throws something out that you love... 'Oh no, now it's gone forever.' I think what the person really means is, 'Well, one day I'm gonna be gone forever. This relationship is over, it's gone forever...' I think, in so many ways, we're constantly combing through this crisis of mortality in all these little forms. It's a very natural thing if you think about it, what it means to be human, and I do it myself all the time, to collect things. I have all these things, like I was talking about - this room - that are precious and can never die. But they're all comforts in a way to deflect from the finality of things, and sometimes you need that, especially in songwriting. If you're really poking at a pretty heavy concept, sometimes you want to be comforted, because you just don't want it to eat you alive.

CDM: How much of being 'gone' and 'home' do you think of as a mental presence, as opposed to a physical one?

JACK: It's very mental to me. I think of the ideas of 'gone' and 'home' in a very mental place. I think of home as a state of being, I think of gone as a state of being. I think we all as people have both going on, and sometimes it's more of one or the other, and your comfort or your awareness in life is when you're gone beautiful things can happen, or when you're home beautiful things can happen - or the opposite for both. I just see those two parts of myself and I feel them intensely.

CDM: It kind of reminds me of in 'Don’t Go Dark' where you say, "Cause I’ve slept in my bed alone next to my girl." Why is being alone mentally, even though you might physically not be alone, such a hard thing to come to terms with?

JACK: That song is about a relationship, and to me, feeling alone with somebody who you care about and love, is dark. It's the end of something. You can feel alone with a stranger, of course, you could feel alone walking in New York City or Auckland, and there are tons of people around but somehow you feel alone. But if you feel alone with a person whose presence in your life is for each of you to give each other the opposite of loneliness, that's kind of a wow moment where you're like: Something's not right here.

CDM: I think in that song as well, especially when you hear the other voices kind of coming in at the end, it's interesting how it kind of juxtaposes that idea of loneliness.

JACK: That's interesting, I didn't think about it that way. I always felt like those voices are sort of pushing me through. They're my friends cheering me on or something. <laughs>

CDM: One of the most powerful lyrics in 'Chinatown' are, "And I'll wear your sadness like it's mine." I think one of the most powerful parts of a strong romantic relationship or friendship can be sharing an emotion, and lending a hand in helping another person go through one of the hardest parts of life...

JACK: And to carry someone's emotions, but not like a burden.

CDM: Do you think it can be hard, to get to that emotional level with someone?

JACK: I think it's super hard, and I think it can be devastating, and that's why to me, it was such a romantic lyric to just throw it away. If I wrote a whole big, heavy song called 'I'll Wear Your Sadness Like It's Mine', it would play into how intense that concept is, but to chuck it out there, like it's nothing... I don't even really sort of go back to it, it's passing. That, to me, is very intentional to just say, 'That's the level of swept up I am in this,' like, I'll take all those risks. Because those are the big risks of falling in love and relationships. Is this person's sadness going to break me? I see it's going to break them. And when you're standing at the ledge, and you're just like, 'Fuck it, I'll wear your sadness like it's mine, I don't even care,' it's a really rare place to be. I guess you'd call it falling in love.

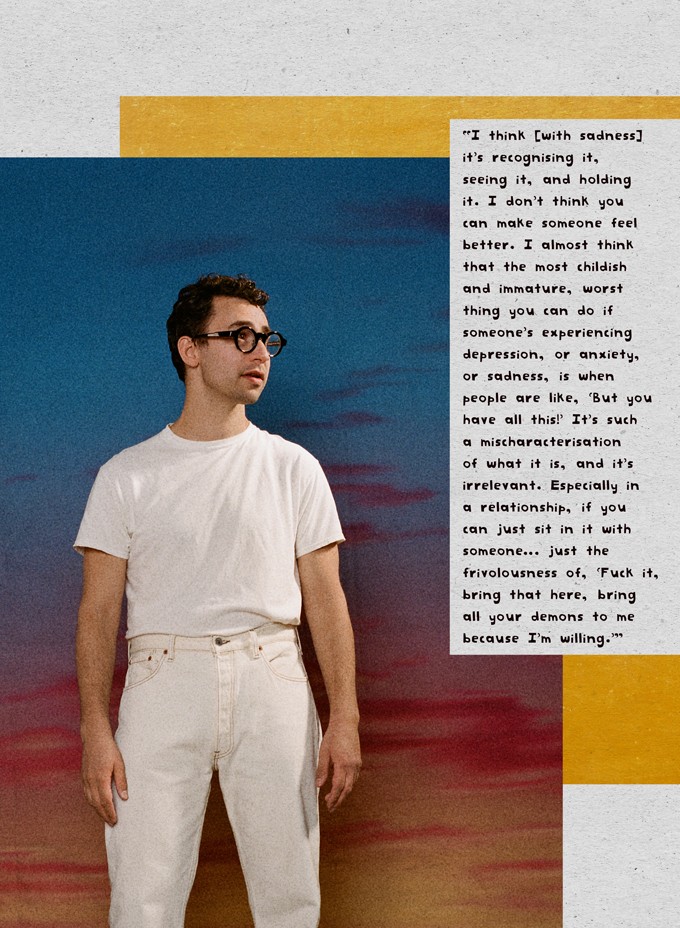

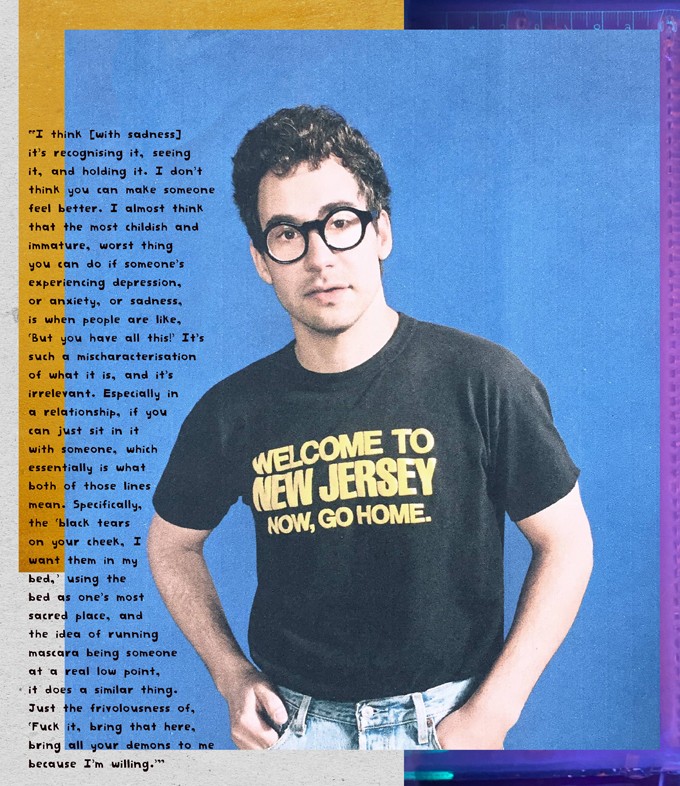

CDM: You confront a similar topic in the lyric, "Black tears on your cheek / I want them in my bed." How do you think you can help other people with their sadness? Sometimes just being there for them is enough, even though it feels like you aren’t really doing anything.

JACK: I think it's recognising it, seeing it, and holding it. I don't think you can make someone feel better. I almost think that the most childish and immature, worst thing you can do if someone's experiencing depression, or anxiety, or sadness, is when people are like, "But you have all this!" It's such a mischaracterisation of what it is, and it's irrelevant. Especially in a relationship, if you can just sit in it with someone, which essentially is what both of those lines mean. Specifically, the "black tears on your cheek, I want them my bed," using the bed as one's most sacred place, and the idea of running mascara being someone at a real low point, it does a similar thing. Just the frivolousness of, 'Fuck it. Bring that here. Bring all your demons to me because I'm willing.'

CDM: Especially in the past year, everyone's been going through so much more trauma, and it's hard. You always want to be there and help, but you don't want to try and be a therapist. There's a fine line between sitting there and being there for them and then actually offering help.

JACK: Also a lot of people don't want you to be there, and don't make space. You have to recognise that there's being there because someone needs it and you can offer it, and then there's this weird human need to fix your friends and family, which is so interesting. I mostly write about this concept in relationships, because to have a successful relationship, you have to be there. That to me is this really interesting barrier - maybe some friends think you're there, some friends don't. Maybe on a good day you are, on a bad day, you're not. But to have a relationship, you have to be there. You have to hold someone's sadness. That's a really interesting line to me. Am I capable of that? How does this work? I have so many questions about it. Sometimes I'm prosecuting it, and then other times in songs like 'Chinatown', which are just romantic dream sequences, I'm just like, 'Yeah, fuck it, whatever.'

CDM: Is it something that people get better at as they go through life?

JACK: You hope. I think people either grow one way or the other in that department, I think you can grow more open and loving, and I think space for people you love's darkness can be an endless space that you can hold; that won't tear you down. I think that comes through knowing yourself. But I also think a lot of people can go the other way, and that can shrink and you can get more and more twisted and complex and within that process have less and less space for the people you love. This is why the greatest thing you can do for the people you love is to fucking work on yourself, because that's how you can be present for them.

CDM: Is it a surreal feeling, to know that your music is there for people who are going through similar feelings of depression/anxiety/loss? Is it something you are very aware of?

JACK: It's surreal if I imagine an amount of people. In concept alone, it's not surreal because I don't imagine my audience to be any different than me. I don't think they're smarter, I don't think I'm smarter, I think we're in a conversation together - the same way I would be with anyone I cherish and care about, and the longer that goes on, I think about this a lot with the release of this album because there's so much context in 'Strange Desire' and 'Gone Now'. My audience knows about me, they know things I've been through, and there's a lot of context to why I'm here and what I'm talking about. So if I think about the scale of how many people may listen, or something like that, that can be an interesting thought. Or when you play shows, there's a lot of people there. You're like, 'Whoah, that's not a normal experience that most people have.' But the idea of sharing, and then they're sharing back and it's this conversation, that's very much by design, and I don't think I would do it any other way.

CDM: Your songs have always touched on loss and anxiety and depression; emotions that I think have really come to the forefront of people's lives in the past year. Songs like 'Everybody Lost Somebody' feel even more pertinent. We’ve spoken before about how your songs change when you release them and they belong to the listener - I was wondering whether that's something you’ve thought much more about in the last year or so, where people have been relying on music in an even bigger way?

JACK: I see the ownership transfer, it's almost like we become a committee or something. <laughs> When I'm working on it, it's mine, and very few people even know, a lot of it even only exists in my head. Then you release it and it's still mine, but it's more like it's ours, and we've formed a board. The board meets and I'm like, 'Well, this is what this is about.' And someone's like, 'Yeah, but you said this,' and I'm like, 'Good point.' Because the truth is, you don't write about things that you know, you write about things that you want to know. This happens to me every time I make a record, I'm always a year or two ahead of myself. Even now when I listen back, I'm like, 'Jesus Christ, I knew this, I knew that, but it was just a sandpaper feeling inside me. I wasn't sure of it.' So the process of hearing it through people who know you; your audience, it does become like a committee where I'm like, 'Oh yeah, good point.' Then we define how we react to it together. I thought 'Let's Get Married' was this brooding loud song; it was sad and weird. Everyone was like, 'No, this is a party. It's a celebration of joy and love.' I thought 'Everybody Lost Somebody'... I don't know how I thought this... I knew it was heavy, but I didn't see it quite as... I think it's easy to write a lyric like that, "Looking like everybody, knowing everybody lost somebody." But when you're with people, and you're saying that together, I was like, 'Oh, okay.'

CDM: It's everybody. Everyone. Not just the concept of 'everybody' when you're in your studio alone.

JACK: Totally. When I say "everybody" when I'm alone in the room, I mean it like, everybody, i.e. all the people, right? When I say "everybody" when I'm on stage with my audience, I mean us. And that's a very different experience, it's a bigger experience.

CDM: I can imagine a really whimsical sketch of an album being released, and all these characters on a board discussing it.

JACK: I would love that. As I said, I'm not like, 'This is what it is, this is exactly what it is, listen to it this way.' I'm free-associating a lot of these things. I'm trying to understand these parts of myself and the world of things I see in other people. It's truly a conversation and no one's right, no one's wrong, we're just trying to figure it the fuck out.

CDM: You mentioned to Zane Lowe that 'How Dare You Want More' touches on when you "found out some secrets about my family." I always think it’s interesting coming to terms with the idea that your parents aren't these mythical figures, but are actually real people with real flaws and secrets?

JACK: It was oddly later for me because I lost my sister when I was 18. She was sick for a decent amount of her life. So since I was five years old, when she was born, we had this intense thing in our family. It was a really tragic experience, but a thing can happen with a heavy trauma where everything is... You don't feel good? It's because of that. You're depressed? It's because of that. Your parents have a weird relationship? It's because of that. So in a weird way, I became super well-versed in the language of grief and loss, but I didn't understand a lot of other things that I think people who don't have that understand, because they don't have this big bucket to just throw everything into. Whereas if you have a big life event, a big trauma, or a big tragedy, it's very easy to put everything there. But the truth is, my parents had some weird shit going on well before that. There are some rubs in the structure of things, in communication, well before that. I think it took me longer than others to sort of look at a lot of that and realise, there's some stuff here that's off, that has nothing to do with this [trauma]. I've actually begun writing about that too, just how weird and complicated it is, it's almost like you're honouring the trauma by letting it be the cause of everything - that I'm fucked up because of this thing, and it's all relative to that. The truth is, there's a lot of shit going on. So I think I became really versed in the language of grief, but then a child in terms of my knowledge of some other things about my family structure. And that came in with 'How Dare You Want More', I just started seeing so many people in my life who felt so much shame about wanting to find joy and wanting to break into the next phase of their life. I'm talking to myself, with 'Stop Making This Hurt' and 'How Dare You Want More', but it's a good device to be like, why is it so shameful to want a better life?

CDM: "Who am I without this weight on my shoulder?" you go on to say. Is how people cope with grief and loss important in creating who they are as a person? Like, the way someone deals with the hardest parts of life?

JACK: That's exactly it. It becomes your identity because you feel like you must make sense of this, so then you hold it, and you almost feel pride about it. It has, in many ways, shaped you into who you are, but there's a dark side to that. The beautiful side is, 'This is who I am, and I own it, and it's complicated and beautiful.' The dark side is, 'Well, am I hanging on to this a little too heavy and stopping myself from experiencing a lot of things because I'm complex?' When the truth is a lot less complex about finding love and joy and things like that. That's a question I pose to myself a million times in my head and therapy all day. Who am I, if I drop some of this shit?

CDM: I'm not sure if you've watched the Marvel TV show, 'WandaVision', but there's a quote about grief from it that I like.

JACK: I haven't. What is it?

CDM: The character Vision says, "But what is grief, if not love persevering?"

JACK: Oh, that's amazing.

CDM: I think about that quote all the time, and I actually was thinking about it while listening to this album because so much of grief and love, I feel like for you, is so interwoven.

JACK: That's beautiful. It is. That's part of that trauma. But also, if you experience loss in one hand like we've been talking about, it can colour things the wrong way. But it's also sort of a secret about what's going to happen here and what it's all about.

CDM: In 'Big Life' you sing, "I wanna know the part of you that light doesn't touch / I wanna know what happens when we're bored in love." The idea of the shadow is something you’ve always explored in your music - in both a literal place, like the contrast between New Jersey and New York, but also in the way you consider humanity, and the parts of ourselves that we hide from the world. Does knowing someone, truly knowing someone, is that when you embrace even the 'shadow' version of them?

JACK: Totally. When you can really see the complicated parts of people, and if you can really take a look at that, and have peace with it, then that's emotionally worth a lot. And you look forward to that when you meet people you might be infatuated with, or you think they could mean a lot to you, you almost want to jump cut to like, 'Show me the worst of it.' You know, 'Let's get right to it and figure out if...' And that's a romantic concept, to want that. It's similar to, "I'll wear your sadness like it's mine." Give me the worst of you. I'm up for it.

CDM: In 'Anna Karenina', Leo Tolstoy wrote, "All the beauty of life is made up of light and shadow." I feel like it kind of encapsulates that acknowledgement of both the light and the darkness.

JACK: Yeah, I think a ton about it. I'm very, obviously, like you said, just geographically, emotionally, and personally, things I've been through that feel like they cast certain shadows, I see things in the light or the dark/shadow. The parts of myself that sort of function in the shadows, the parts of myself that are happy to fly out into the light, that's how I've always felt.

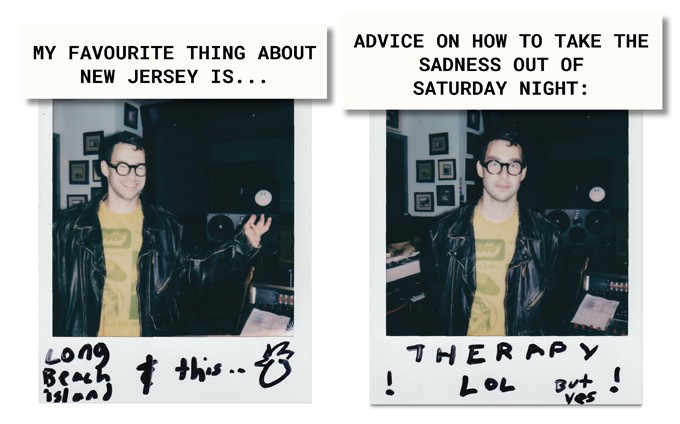

CDM: "I got a car and a bike and I’m free as a wheel," you say in 'Big Life'. What does freedom mean to you?

JACK: I literally got a car, then I got a bike, and I just started driving around, going down to the beach in New Jersey, being on my bike and just flying around and it was just the literal movement of it. It's an oddly literal line. I reached this point in my life, I didn't have a license for so long, and I got it done during the pandemic and I was like, 'I could do anything! I go anywhere.' It blew my mind and it was a silly thought, like, 'I'm in motion.' But then it tied into the song because the song is really this question: "I'm after a big life, is it you?" That's the real question. I like myself driving around on my bike and I'm just trying to find it, and the song poses the question, "Is it you?" Freedom to me is motion, it always has been.

CDM: In both 'Big Life' and 'Secret Life' you consider ideas of boredom and love ("I wanna know what happens when we're bored in love" and "where you and I can get bored out our minds"). Why do you think that's something you keep coming back to in those songs?

JACK: Because I think when the chemicals wear off, is when the beauty begins, you know? When you make the choice, when you say, 'All right, I'm here, I'm in my body, my feet are planted on the ground, and I choose this every day.' I think it's just the height of consciousness in a relationship. I am also using boredom as almost a fancy or funnier word for real. When you've heard all my jokes, when you've done all this, we've done all that, and we're still here. It's a sentiment I think about a lot.

CDM: ‘Secret Life’ is officially one of my favourite Bleachers songs to date! At what point did Lana Del Rey's vocals end up on that song?

JACK: We were in New York. She was hanging out at the studio and I just played it for her, and one thing led to another. It was interesting because she wrote, 'Don't Go Dark' with me, and sings a little bit on it, but with 'Secret Life' I featured her way more. The tempo, and the key, and the way I sang it - my vocal is very direct and centred, so I liked the idea of this female voice being like a dream, almost the person I'm talking to about this.

CDM: The Chicks’ voices appearing alongside Lana on 'Don’t Go Dark' sound so beautiful. How did that come together too?

JACK: Similar story, I was in the studio with them, I played them it and they were like, 'That's cool.' And I was like, 'Come sing on it.' It's always something loose and fun. Also, if you're going to have your friends sort of pop in, then you should sort of record it the way you intended, which is your friends popping in.

CDM: In the last two songs on the new album, you touch quite a lot on your relationship with your faith ("What you thought was faith / That was hollow" in 'Strange Behaviour' and "ain’t no faith can take your place" in 'All This Faith'), and I feel like mentions of the 'preacher' have always been a running idea through the Bleachers discography as well. What’s your relationship like with faith, currently?

JACK: It's loose, and it's heavy. It's interesting... I think in the world I grew up in, and maybe it's similar to yours, concepts like faith get really co-opted by organisers of religion. So I was deemed faithless, or godless, or any of those things. It was always really tough for me because I'm filled with faith and hope, and magical ideas about things, but didn't fit into anything too specific, so it can sort of label you as someone that you're not. That line hit me like a ton of bricks, "What do I do with all this faith?" Because that line is in direct contrast to that, it's sort of like every piece of me is boiling over with faith and hope, and I have no God to put it in, right? I just have my work, and the people I love, and my audience. But then at the end, I kind of wrap it around, which is about my sister, "Ain't no faith can take your place," but that sort of serves to work with your quote about loss or longing being the existence of love, the idea that she or that experience is the embodiment of faith. And that if I could spend an entire song saying I'm bursting with faith, but it's still nothing compared to you, it almost became a way that I can imagine explaining my faith. If someone says, 'Do you believe in God? Are you part of organised religion?' I would be like, 'No, but I don't know what to do with all this faith, there's nowhere I can put it.'

CDM: Yeah, there's still something--

JACK: And it's not even something; it's massive. It's all around me. I think about it a lot. And I'd like to write more about it at some point.

CDM: 'Strange Behavior' was originally a Steel Train song - what made you decide to revisit and include it on this new album?

JACK: It's such an interesting one. I sat down on my piano and I just started playing the song called 'Women I Belong To', which is an old Steel Train song, because I liked the structure of how I wrote it, and I hadn't played in a while. Then I was playing other songs. I played a song called 'The Speedway Motor Racers Club'. Then I started playing 'Strange Behavior'. I was just playing on the piano. To your point about some of the tie-ins with the last song ['What’d I Do With All This Faith?'], I was just like, 'Jesus, this is like a brother or sister to some of these later album statements.' I went into the room where I am now, down the hall, and I just recorded a pretty quiet version. I found it really powerful. And then I started dressing it up, with the horns and whatnot. But it was pretty... I sort of stumbled upon it. I don't really listen to things from the past, but it hit me and I felt like I'd written it that day, even though I didn't.

CDM: There exists a Bleachers song called 'Shadow Of The City' that you have only ever performed live, circa 2016. Which came first, the festival idea, or the song?

JACK: Both. I kind of had the idea for it [the festival] and then I was like, 'I want to write a song.' I always thought, 'I'll just play it once at the festival and never play it again. It could be this weird theme song to the event.' But I don't know, I got too excited, and I didn't love the song as much as I loved the festival. So the song kind of drifted, but the festival exists. <laughs>

CDM: Maybe the song will come back one day?

JACK: One day. The chorus was good, I never really got everything else right.

CDM: Are there more songs that didn’t make the new album? In the tracklist story you posted it looked longer than ten songs...

JACK: Not really. I always wanted this one to be pretty short because it's very dense. I'm getting into a lot. So I wanted it to be like a very intense conversation. When I have intense conversations with people, if they go too long, I lose some of the... it's meant to be listened to over and over again. I didn't want to overstuff it, so there aren't, there are little ideas, but not really.

CDM: Does that kind of tie into why there was no 'I'm Ready To Move On' reprise for this album?

JACK: I didn't feel it. When I started making the album, I was like, 'I'll probably do that. That's sort of like my thing.' But albums, they tell you what they are; you have so much less control than you imagine. In the process of making it I was like, 'This is almost the opposite of that, I don't need to make that statement.' The 'I'm Ready To Move On' concept is this finality and then it's this breath of fresh air after. This one sort of goes in and in and in until you end up with this... you're looking at this thing and saying, 'What'd I Do With All This Faith?' This body of work wasn't designed to end in that way.

CDM: In the 2015 ‘Like A River Runs’ release you included a 15-minute recording of you and your therapist talking about dreams ('Dreams Aren’t Random') where you try to decode the meaning behind some of your recurring dreams. Do you still have any vivid or recurring dreams now?

JACK: Yeah, I've been writing them down. I would like to do a different version of that in some way. I like the idea of some of these discussions about subconscious set to pieces of music.

CDM: Will you ever make another Red Hearse album?

JACK: I'd like to! I love that album. I love Sam [Dew] and [Soun]Wave. We're kind of always off doing our own stuff, but we actually talked about it the other day. I really would like to.

CDM: What happened to your book, 'Record Store'?

JACK: Working... It's sort of shifted in tone, but I'm working on something.

CDM: Talk to me about the recurring imagery of tomatoes with this album cycle…

JACK: The tomato is the state vegetable of New Jersey, but it's a fruit. I thought that was so bizarre because all the totems - there's the broken bottle which is sort of like a broken relationship, the car which is about running, the bleachers which are the band, and then the tomato is New Jersey. I thought it was such a funny way to do it because tomatoes are fruit, but they're the New Jersey State vegetable, and that feels so connected to this place in the funniest way. So it just has become a symbol of the band somehow.

CDM: Lastly, I want to hear about your other visits to New Zealand! Did you get to do much sightseeing/exploring while you were last here during Summer 2019 to work on the new Lorde album?

JACK: I've done a decent amount. Ella is such a close friend, who I talk to just about every day, and New Zealand and the culture is such a massive part of her life and her emotional life, and I feel like I get so much through her from it. So it's become a place that I feel extremely close to and hope I can come to a lot more. I'm not trying to offend any other countries, and I have close ties with America; I've been touring here forever, but I feel an intense closeness to New Zealand.

The new Bleachers album 'Take The Sadness Out Of Saturday Night' is out now.

Watch a live video for 'How Dare You Want More' below...

Jack Antonoff

Jack Antonoff