Interview: The Neighbourhood's Jesse Rutherford on 'Chip Chrome & The Mono-Tones'.

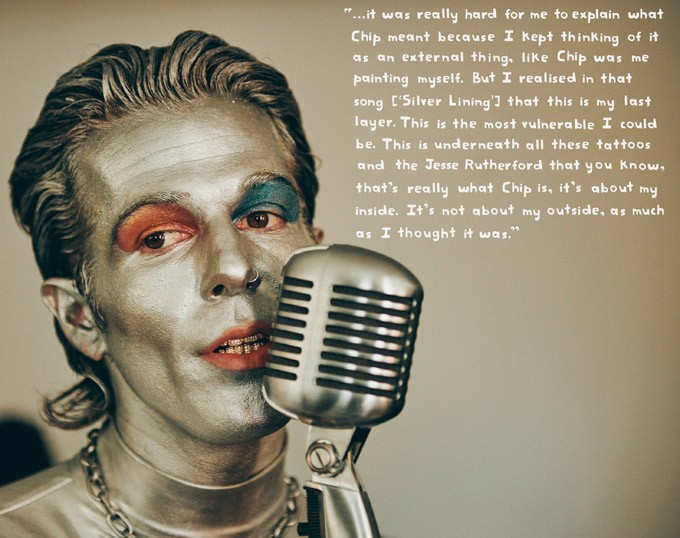

A week out from the release of their new album, ‘Chip Chrome & The Mono-Tones’, The Neighbourhood's frontman Jesse Rutherford has an odd calmness about him. Pausing to reflect, he says, “I'm relieved; I'm more relaxed than usual about it, I think I've been more anxious in the past.” Instead of the relatable anxiety of sharing a new project with the world, Rutherford has found a clarity of self through Chip Chrome, a head-to-toe scintillatingly silver hero whose voice narrates the 11 tracks. Though reinterpreting his narrative through his alter-ego, the album delves into the purest and most honest truths from Rutherford himself. He sums it up best: "That's really what Chip is, it's about my inside. It's not about my outside, as much as I thought it was.”

The album itself clocks in at just 31 minutes in total, but despite its short span, this is what The Neighbourhood living their best life sounds like. Album opener 'Chip Chrome' introduces listeners to a fantastical, surreal world, and the ten tracks that follow see the band exploring a plethora of musical ideas, from the country-twang of 'Hell Or High Water', to the hip-hop infused 'BooHoo', and The Manhattans' sample (from their 1973 song 'Wish That You Were Mine') that begins the vivacious 'Lost In Translation'. Amongst it all, the band feel more comfortable than ever with their unconventionality and ever-changing sound.

The Neighbourhood might have found it hard to imagine ever changing, but with their evolved technicolour vision, Rutherford steps into the light as Chip Chrome, embracing the transformative iridescence of seeing the world anew with rose-tinted glasses. "Colour helps to express light - not the physical phenomenon, but the only light that really exists, that in the artist's brain," mused French artist Henri Matisse, and Rutherford's inner flame burns brightly indeed on sincere songs such as 'Hell or High Water' and ‘Pretty Boy’.

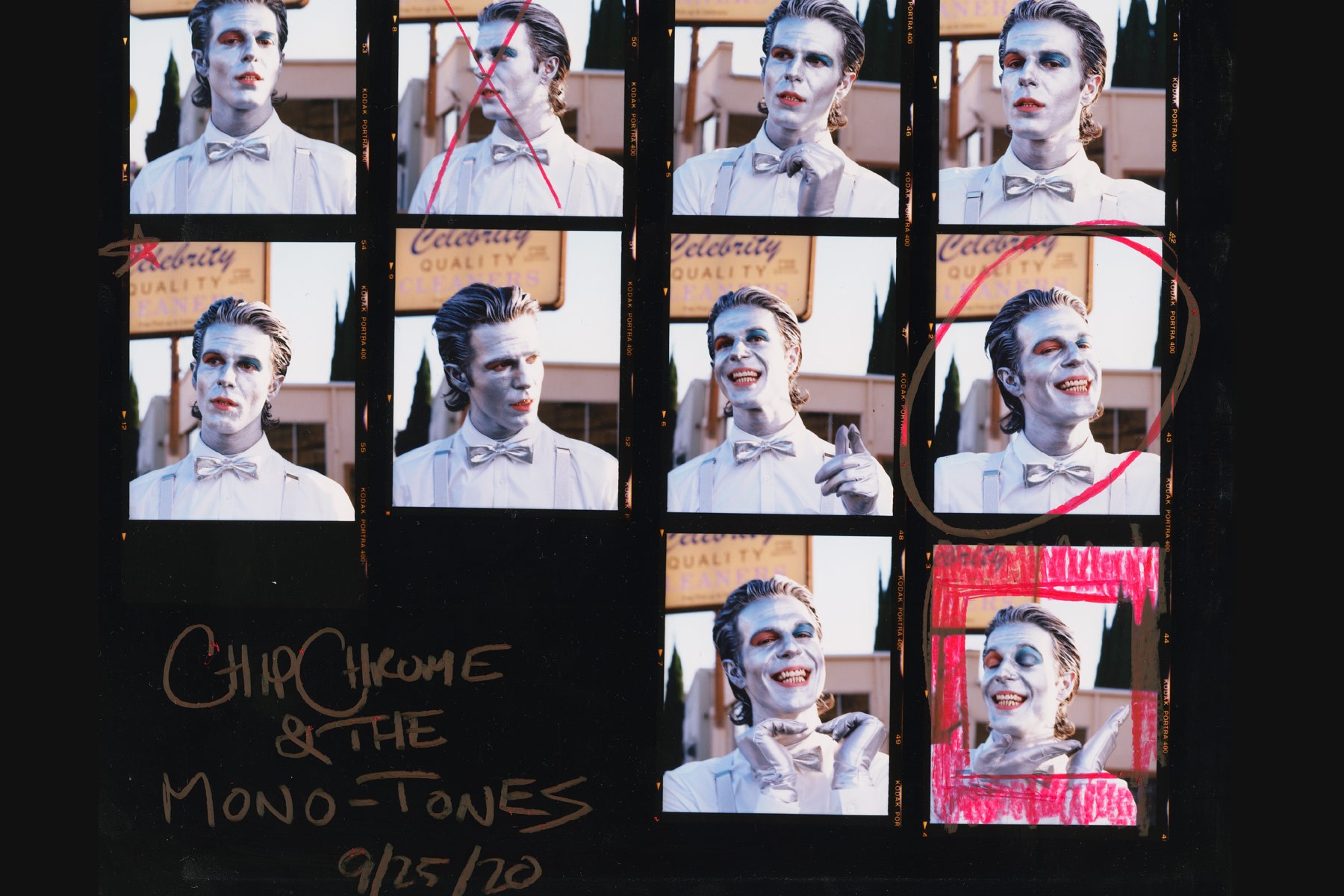

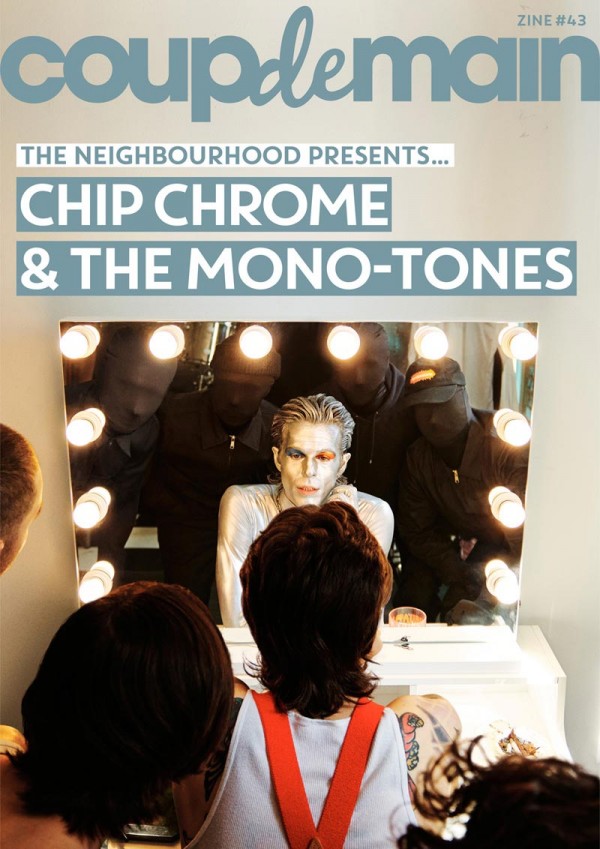

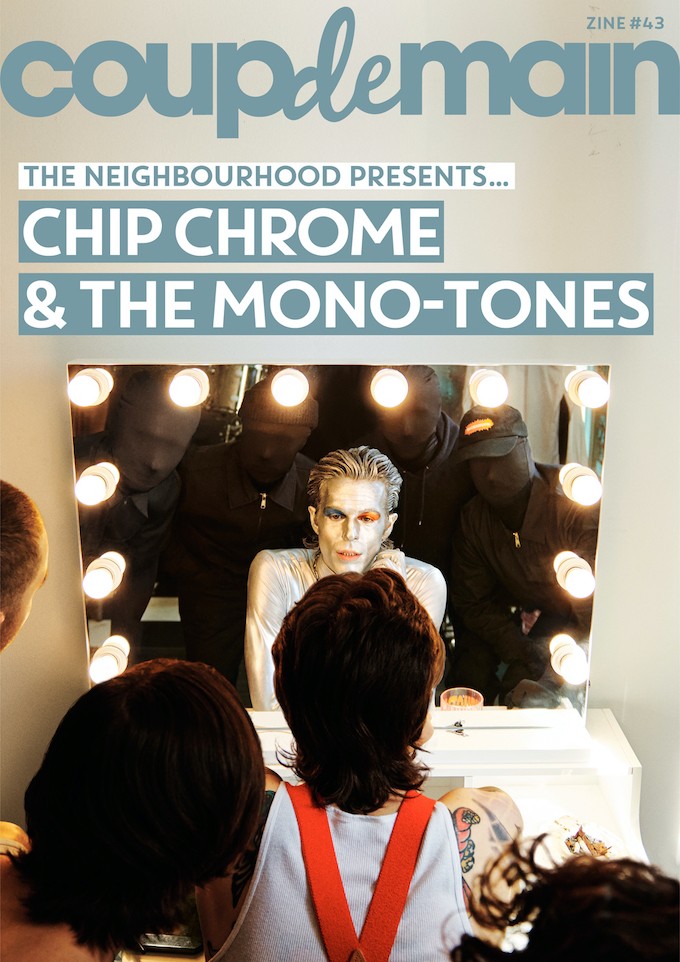

Click here to order a CDM x The Neighbourhood zine (i.e. a mini-magazine featuring photos and quotes from this cover-story).

Flanked by The Mono-Tones, a.k.a. Rutherford's bandmates Brandon Fried, Jeremy Freedman, Mikey Margott, and Zachary Abels, the five-piece truly commit to the album's concept, giving the space for Chip Chrome to truly shine. Rutherford sings in ‘Devil’s Advocate’ that he's married to his friends, and though that can come with difficulties, he states definitively that, "We're a democracy, we have to figure out how to make something work for all of us, and we don't always agree on stuff."

It's been a long road for The Neighbourhood, who first formed back in 2011 and saw early success with 'Sweater Weather', which has since gone Platinum five times in the United States - something which Rutherford spent a long time trying to replicate, confiding that, "I kept asking myself: How did I do 'Sweater Weather'?" He came to the realisation that it took disconnecting entirely, both from social media and the expectations of others, to create a product which was completely unique. In the very brief interlude 'The Mono-Tones', he acknowledges the confusion that other people's opinions can cause ("Everyone screamin' makin' too much noise, I can't hear myself anymore," he sings in a pitch-shifted voice).

“Mainly at the core, my songs are about relationships,” Rutherford explained in an episode of his Therapy Records podcast (a publishing company he recently launched alongside new album co-producer Danny Parra), and through Chip Chrome, Rutherford's storytelling reaches its height of vulnerability - whether it be in 'BooHoo' where he sings about the insecurities of his own relationship, or the eternally optimistic 'Silver Lining'.

This new album also marks the band's final release via Columbia Records, giving the five-piece total freedom with what they choose to do next. Having released music and toured relentlessly for the past nine years - with opening acts such as The 1975, Kevin Abstract, and Travis Scott, as well as Rutherford having been invited by Lana Del Rey to perform 'Daddy Issues' live together on-stage last year at the Hollywood Bowl - The Neighbourhood are on the precipice of an unknown, that they are in full control of. Though their tour in support of the new album has been rescheduled to 2021, fans across the world are eager to see the new project imagined live.

In the 'Middle Of Somewhere' tour documentary released late last year, Rutherford narrated that: "This gets me so calm. When I was a kid, I feel like every time I was drawing or doing something, making a graphic in photoshop, when I'm zoned in on something... You know that feeling when you're zoned in on something? You're so at peace. It's so nice." And with 'Chip Chrome & The Mono-Tones', The Neighbourhood find themselves well and truly zoned in and basking in the afterglow of their previous releases - which brought to fruition a drive for them to create their best work. This time, there’s nothing lost in translation.

COUP DE MAIN: On 'Wiped Out' you had 'A Moment Of Silence' to introduce the album, and on 'Chip Chrome & The Mono-Tones' you have 'Chip Chrome', this 30-second introduction which feels intergalactic or like 'The Wizard Of Oz' when everything in a film gets very fantastical and surreal. What made you want to start the album with this intro?

THE NEIGHBOURHOOD - JESSE RUTHERFORD: We got this new piece of equipment called a Moog One - it's a really badass synthesiser. I don't know how to use it, but it's cool. It was the first night, I think, we had that song and that piece of equipment, and we were playing around with it. That sound ended up happening and we had it for a long time and always were trying to figure out what to do with it. But it was such a good spice to put on the album, once we completed the whole tracklist and everything, it felt like it was just the right amount of flavour and nuance to give to the surrounding and to the core of the songs. It also reminds us of the THX movie intro, when you start a movie. It just feels like a grand entrance, like a landing, or entering this new fantastic space.

CDM: The sentiment of 'Pretty Boy' is so pure and heartfelt and reminds me of a quote from the writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in which he said: "Love is not just looking at each other, it's looking in the same direction." Do you agree or disagree with that opinion?

JESSE: I so agree. So much of the theme of this album has to do with that, and with the band too. We're a democracy, we have to figure out how to make something work for all of us, and we don't always agree on stuff. That's part of it: 'What's best for the whole idea? And what is the idea? What are we trying to do here?' So I totally agree with that. I feel like you have to start with the love inside your ecosystem. And if you're not able to agree with each other, whether it's your band or your partner, or your family, it's pretty hard to move and to go anywhere from there.

CDM: Chip feels like a real romantic in 'Pretty Boy' (singing, "As long as I got you / I'm gonna be all right / As long as I got you / I'm not afraid to die"). When you were writing songs for this album and putting yourself into Chip, how did Chip fit into the world compared to Jesse?

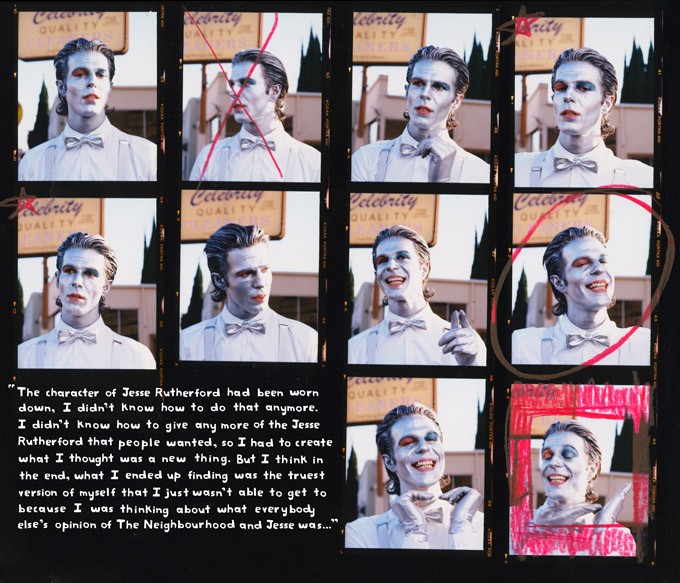

JESSE: I'm still trying to figure that out. The band needed a true leader and I think that the audience deserved the maximum amount of entertainment possible from what we were able to control. You can't always control if Spotify and Apple and CDM are going to put you on the cover. You can hope for it, but unless you create something genuine enough... At least this is what I'm learning now, like, why we ever had success is because it was coming from a genuine enough and vulnerable enough space. But [Chip and Jesse], I didn't always attach the two. Then by the time the album was finished, at the end of writing when I wrote 'Silver Lining', that song kind of made me realise, "Oh, this is about that exact thing, a last hope." 'Pretty Boy' could have only happened, and the album could have only happened with the time in between album one until now, or even album three until album four. It required that. Time was part of the recipe. The character of Jesse Rutherford had been worn down, I didn't know how to do that anymore. I didn't know how to give any more of the Jesse Rutherford that people wanted, so I had to create what I thought was a new thing. But I think in the end, what I ended up finding was the truest version of myself that I just wasn't able to get to because I was thinking about what everybody else's opinion of The Neighbourhood and Jesse was.

CDM: It must be hard as an artist when you're performing and putting out music as yourself and people perceive it in a certain way. Is it easier for you to have something like Chip - a whole new 'character'?

JESSE: That was a big part of it for me. I wanted to separate. There are so many reasons why I did the Chip thing. Like, the aesthetic of it. Originally, when I first thought of it and why I wanted to attach it with the band, a lot of it just had to do with wanting to feel worthy of the attention that I was getting... I got off the internet for a while. That really helped me because I was very challenged by the idea that you could work on a song for eight months and post the art for it, and it gets 36,000 likes, but if I post a picture of me and my girlfriend, it gets 150,000 likes, and that's not why I'm here. I love that part personally, but that part is what people obsess over now, and that's not why I got into this and it's not why I wanted to be on the internet in the first place, or why I got addicted to it in the first place. I got addicted to it because it was a way for me to be creative and to be able to create worlds and aesthetics and I feel like that got lost. Then I lost touch of what I was there for, and what my opinion was at all because you just keep looking at these numbers and all these opinions all the time, and that really twisted me up. So I just wanted to separate that, so I could know who Jesse was, and so I could put the most Jesse into the art, but by creating something. Like when I created The Neighbourhood, it was the same thing as Chip. It was a filter. It was black and white. It was a big idea that I had a visual for and then I was able to soundtrack it. That's the exact thing that happened this time around with Chip, except now, the audience has also been informed of who I am, or who you think I am, as far as what I've given, which is all truth; I've been vulnerable. Sorry, I get confused even thinking about it... It's tricky. I just wanted to separate my personal life from the art and be able to put more of who I personally am into the art without looking at what people were thinking the whole time.

CDM: There’s a scream at the end of 'Pretty Boy'. What does that signify? Was it just an outburst that happened during recording?

JESSE: Sean [Dwyer], he assisted Danny [Parra] who produced the record with us, and he turned into one of our closest friends. He's a great person. That scream describes him and his essence in a nutshell so perfectly. It was at the end of the take of that song, I think Jeremy [Freedman] was recording keyboard parts, and he had just finished it. Sean was in the tracking room with Danny, so Jeremy was out recording in a different room. Then Sean, just at that moment, just felt that and just did it, and then we just ended up keeping it because it described a lot of our feelings on getting to the end of that song. I think this whole fucking album is just a more realised version of what we've been trying to do. So we kept it, because it was just too perfect.

CDM: I love it. Lots of people have been theorising what it means about Chip. It's interesting how people have taken it and run with different stories.

JESSE: I can't look at anything. I don't look at anything - any numbers, any comments, I can't do it anymore. But it's working, not looking at it is working!

CDM: ‘Lost In Translation’ is definitely an album highlight for me. How did that song come about? Did it exist before you added the sample of The Manhattans’ song, or was the sample the basis on which it was created?

JESSE: There were two different things. Zach [Abels] had come in and had the progression that he was playing on the keyboard, and then we jammed and wrote the song around that, like the verse and the hook. Brandon [Fried] makes beats all the time, and he samples all sorts of shit. One of his beats was called 'Sparkle', and he had sampled 'Wish That You Were Mine' by The Manhattans. I was always like, "We've got to figure out a way to work in Brandon's samples into this album." One night we were just sitting around and mixing things, trying to figure shit out, and then that one ended up working out how it did, and it blew our fucking minds. And then we wrote the pre-chorus after because it also samples that, <sings, "Time, do it to me one more"> progression. So it kind of went back and forth and informed each other. Back to my thing about time being the main ingredient in the recipe of this album, and pun intended with that lyric too, but it took time for that to come along. It gradually turned into what it did.

CDM: In ‘Lost In Translation’ you sing, “Sick of people telling me 'be patient'." It is said that patience is a virtue, and good things come to those who wait, but do you think that in the generation we live in today, people aren’t willing to wait for things?

JESSE: How can we? You could wake up tomorrow and be virally famous and your whole life could change. All of us are implanted with that idea because that happens now. You could be the fucking President tomorrow - look, who is. It's all so immediate, and that's why it is hard right now, and harder than ever. Not only are things shittier than they've ever been, but we're receiving the information of how shitty it is at a crazy rate, and there's so much of it at once. Any sort of change takes time. Like, if every social injustice was solved right now, today, it would take at least fifty years, I would say, of the government redistributing money into other places rather than giving it to the fucking military and the police over and over. It would take time for communities to build and to grow and to have new programming. It's funny, because you ask that question, and I've learned so much about what I was saying in these lyrics now - I feel like I'm reaching so much more understanding of what I was trying to get to. I've solved some of these things. Mikey [Margott] was talking to me about 'Cherry Flavoured' a couple of months ago, and he was like, "Man, I've always loved that song but I don't know how much I ever really listened to your lyrics, but I feel like you're doing what you're saying - you're learning from what you're saying, like I see that in you now." I didn't even think about that until he said that back to me and had some time to reflect back on it. I think that when I started writing 'Lost In Translation' and 'Cherry Flavoured', both of them were pointed at 'you' and the label and everybody else, and feeling like maybe I deserved something? Then by the end of it, I didn't feel like I deserved anything. But would I like to earn some more attention and whatever? I guess, but I don't really deserve anything, I just have to make the changes within myself in order for anything to be reciprocated from the world back onto me.

CDM: You go on to say in that line, "I’m trying to light the fire with no flame." As a creative, is it particularly hard when feeling drained of ideas or inspiration and having to just wait for that ‘flame’ to come?

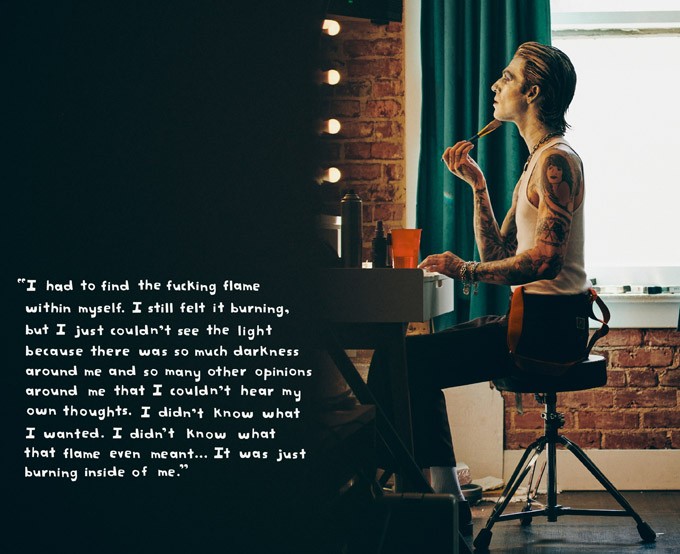

JESSE: It's part of the process. It's easier said than done, but now I know that that's the truth. I had people telling me that for so long. I've learned that now with this process, like all the things you're telling me now, I'm like, 'Oh yeah, I guess I ended up learning that.' I had to find the fucking flame within myself. I still felt it burning, but I just couldn't see the light because there was so much darkness around me and so many other opinions around me that I couldn't hear my own thoughts. I didn't know what I wanted. I didn't know what that flame even meant... It was just burning inside of me.

CDM: ‘Lost in Translation’ touches on a struggle in communication which I feel like is something that we all struggle with. 2020 has really highlighted how we communicate with other people - I read a New York Times article recently about how everyone is becoming social awkward. It said: "Even if you are ensconced in a pandemic pod with a romantic partner or family members, you can still feel lonely - often camouflaged as sadness, irritability, anger and lethargy - because you’re not getting the full range of human interactions that you need, almost like not eating a balanced diet. We underestimate how much we benefit from casual camaraderie at the office, gym, choir practice or art class, not to mention spontaneous exchanges with strangers." Do you agree? Do you think it has impacted the way you are socially?

JESSE: Absolutely. I think I've gotten so much worse, and it scares the fuck out of me. Because it's also my job to be the 'words guy'. There are so many parameters and there are so many more things to be conscious of, and I want to be accountable. But being accountable is very hard. It takes energy. You have to focus on that, and I'm trying, I want to get better at that. Communicating has gotten hard.

CDM: How have you been adapting to socially distanced communication, in your life, with your music, and connecting with fans in a world where you're unable to tour?

JESSE: It's so hard because I'm thriving in a lot of ways. I like rules. I really like rules and constrictions. I like when there are not many options, and it's like, 'Well, I can't even think about that one because there's no exit to get off the freeway there, so I can't get off.' I kind of like that. It makes things more simple.

CDM: Do you find it hard to make decisions when there are lots of options?

JESSE: Fuck yeah, that's why I'm so overwhelmed. I don't know if our brains have the bandwidth for this, there's way too much. It seems like all walls have been broken down. As a society, we're obsessed now with pulling the curtain back and seeing what's behind it, but nobody ever wants to deal with what's behind it. We just want to stare at it and make a reality show out of it and keep watching it.

CDM: In the second episode of your podcast you say you’ve been enjoying listening more than ever - to other people, and to music. Has 2020 become a year of reflection? And just being there for each other?

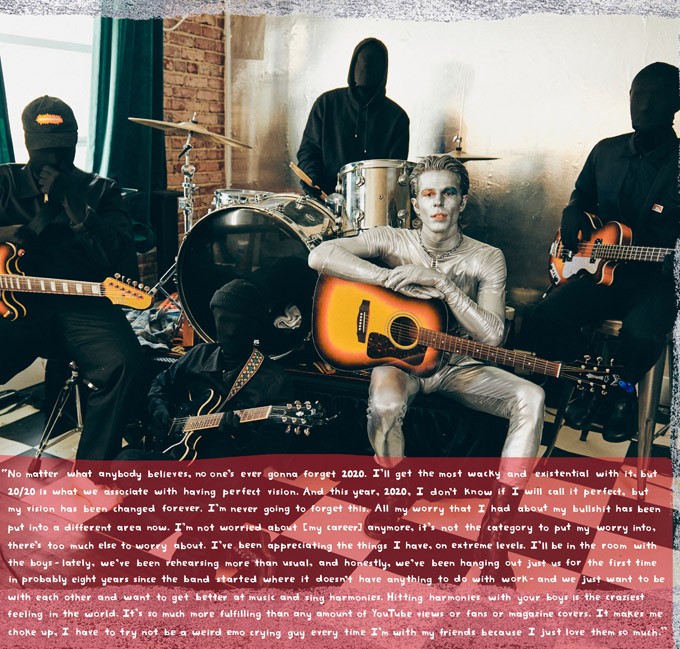

JESSE: Absolutely. It has to be. No matter what anybody believes, no one's ever gonna forget 2020. I'll get the most wacky and existential with it, but 20/20 is what we associate with having perfect vision. And this year, 2020, I don't know if I will call it perfect, but my vision has been changed forever. I'm never going to forget this. All my worry that I had about my bullshit has been put into a different area now. I'm not worried about [my career] anymore, it's not the category to put my worry into, there's too much else to worry about. I've been appreciating the things I have, on extreme levels. I'll be in the room with the boys - lately, we've been rehearsing more than usual, and honestly, we've been hanging out just us for the first time in probably eight years since the band started where it doesn't have anything to do with work - and we just want to be with each other and want to get better at music and sing harmonies. Hitting harmonies with your boys is the craziest feeling in the world. It's so much more fulfilling than any amount of YouTube views or fans or magazine covers. It makes me choke up, I have to try not to be a weird emo crying guy every time I'm with my friends because I just love them so much.

CDM: In ‘Devil’s Advocate’ there’s the line "married all my friends" - is this about your bandmates?

JESSE: For sure.

CDM: I feel like people don't often talk about how relationships are something that you have to be constantly working on. Is that something that you guys are aware of as a band unit, that you are always working on?

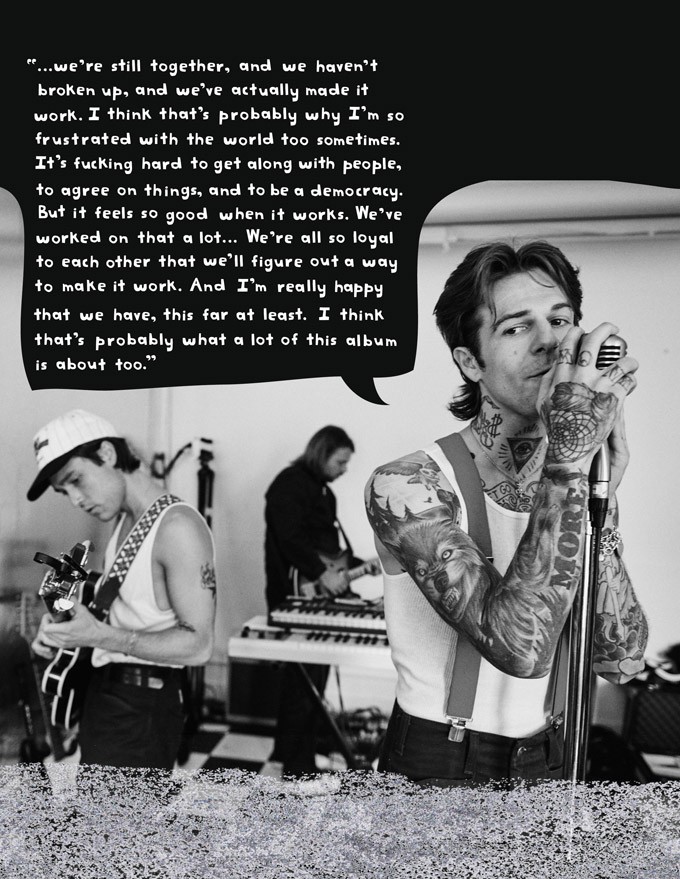

JESSE: Big time. Before we were getting into this record, we were getting into a good place with each other on a personal level anyway. I think that's the only cool part about this band is that we're still together, and we haven't broken up, and we've actually made it work. I think that's probably why I'm so frustrated with the world too sometimes. It's fucking hard to get along with people, to agree on things, and to be a democracy. But it feels so good when it works. We've worked on that a lot, and we've made it work. There were so many times where me and Jeremy just so didn't get along. I would go to the boys without Jeremy being there, like, "I don't know if I can do anything more with him. I don't know if I can do it. I love him, but I don't know if I can do it." We're all so loyal to each other that we'll figure out a way to make it work. And I'm really happy that we have, this far at least. I think that's probably what a lot of this album is about too.

CDM: In ‘Hell Or High Water' you sing, “Each time I fail, it makes me try harder." Is accepting that failure is just a normal part of life an important realisation?

JESSE: Yeah, and to put things into perspective. I agree with what you said.

CDM: People have noticed that those ‘Cherry Flavoured’ lyrics parallel the second verse of 2013’s 'Afraid' ("Sell your soul, not your whole self"). Was that a purposeful parallel, or are the themes of selling your soul something that you think about a lot when writing songs?

JESSE: There are themes that I've definitely been drawn to. I didn't make the parallel, but they're very related. At that time [writing 'Afraid'], I was just about to get signed to a major label, and it's all I wanted, and I was getting that. When I started writing 'Cherry Flavoured', it was a lot pointed at the label. My frustrations, maybe? They're definitely related. I'm just thinking about that. That's crazy.

CDM: It’s interesting to think about 'cherry flavoured conversations'. How they seem nice in theory but also mean that there’s less space to have important conversations. Is the way we present ourselves online also 'cherry flavoured'?

JESSE: Totally. It's another way of saying bullshit. And bullshit is great, I love bullshit - I'm American, I'm addicted to it, we all love it. But it's choosing what bullshit you're intaking. When I started writing the song, as I said, I was pointing it more at other people, thinking, 'You're getting my hopes up, and then you let me down; you don't end up showing up.' But I think later on I ended up realising maybe that was more about me, maybe I was the one that was giving the cherry flavoured conversations and trying to idealise things. Learning how to play guitar and learning how to write songs that way was one of the main ingredients of why this album ended up working how it did, and why I'm feeling a little bit more sane lately. I had to learn how to speak a different language - like, I could talk all day and make things sound great, but if I can't walk the walk, then what does it really mean? I think I just kind of had to take that message in and live with it for a little bit. And I guess I still am.

CDM: Chip is questioning everything at the midway point of the album in ‘The Mono-Tones’. He says, "Don’t know what I'm thinking / What am I doing?" You've mentioned that the Mono-Tones are the voices in your head. Do you think it can be hard to figure out your own thoughts when you’re almost overloaded with different ideas? How do you form opinions?

JESSE: Time; I just need time to think about things alone. Being alone has helped. For me, I have to know when and how to include people around me because all I want to do is feel that sensation of getting an idea across with somebody else. One of the coolest parts of being creative to me is, like I was saying, singing harmonies; when you're doing something with somebody else at the same time. I don't want to do things and get all the credit just because I did it. I like being able to put people in positions and make them shine in the best ways. And help them shine while helping myself shine as well.

CDM: I love the contrast in ‘BooHoo’. The song is so upbeat and feels so jolly, but in it you sing quite openly about anxiety, "You keep on telling me to relax / Doctor got me keeping my cool." You talk a bit about when you first started going to therapy in your podcast, and I was wondering whether you find that songwriting feels like therapy to you? Or do you talk about your songwriting / your music in therapy?

JESSE: I know songwriting is supposed to be my therapy, right? Like, I get to do that. Why do I also need to go talk to somebody about stuff all the time?

CDM: With songwriting, you're sharing that with people

JESSE: With everybody!

CDM: Whereas therapy is a one-on-one experience. There's an assumption that for artists, songwriting is their therapy, and that's how they deal with stuff.

JESSE: For me, I would say both of them are one and the same because at the end of the day, it's about me listening to myself, and learning from that. Like all the songs we've been talking about, even referencing, like, 'Afraid' back in the day. I say how I feel, and in the songs, I articulate it usually better than any shit like this where I get to just go off, and I hate doing this because there's no structure. I'm just gonna sound like an idiot because I'm just gonna go on forever, but they are very related... Sorry, I'm so worn out. I just did this live show for the past two days and have been doing all these interviews. I love it, but I'm just... working. Maybe that was part of it too. When I was five / turning six, I was discovered by people and started acting, and I did that until I was thirteen, and then found music and then knew I wanted that as my career and then got that by the time I was twenty-one. So much of my wellbeing has always been having to do with other people giving me love and attention; that has been my meter as to how I'm doing. I'm trying to fix that because that's not what it's all about. I think in the first album and even 'Wiped Out!', in that moment of The Neighbourhood, and then the time in between then and now, I wasn't always the centre of attention for a while. I had to deal with not being that and having to figure that out on a personal level. Just because that's what I was used to and that's what my programming was. That's not necessarily healthy, but it's just my specific programming. I've just been kind of trying to figure that out. I think I was judging my self-worth based off of how much attention other people were giving me. And that's just not chill. I'm still figuring out how to do that, but I think I've made a lot of progress, especially with the process of this album. I've gotten the results that I wanted. I kept asking myself, like, "How did I do 'Sweater Weather'? Like, what was it? What did I do? How can I do that again for you? What do you need? Is it the progression? Is it the lyrics? What is it? Is it because I did this? Or the tempo of this? Oh, it must be the snare drum, it has to be the snare drum." Or I was trying to be like, "How do I get more of your attention?" I just don't think that's what it's about.

CDM: It's the place it's coming from, right? Not those individual components of it.

JESSE: Yes, it's the moment and what informed that moment, that had nothing to do with any of those other things I'm talking about. I keep going back to this time thing because I have to be more okay with time because nothing happens without time. I'm not gonna go any further without being able to factor that into the situation and knowing that it's not gonna happen immediately, you know?

CDM: You sing in 'Silver Lining' about that last hope. When you're trying to find the silver lining, how can one overcome or avoid obstacles like lightning?

JESSE: Well, I think you only find a silver lining when there's so much negativity that you need to find one thing to be your last hope. Like the lyrics that I say in there, "This could be your last hope, I hope it's all you need." Because after this layer, it's over. I wrote that song last for the album; it was the last one to come out. I think it was really hard for me to explain what Chip meant because I kept thinking of it as an external thing, like Chip was me painting myself. But I realised in that song that this is my last layer. This is the most vulnerable I could be. This is underneath all these tattoos and the Jesse Rutherford that you know, that's really what Chip is, it's about my inside. It's not about my outside, as much as I thought it was.

CDM: So this album is the last album you’re releasing with Columbia, right? You mention in your podcast that you feel like you’ve been super productive since you turned in the album masters. Do you think there’s something freeing about not knowing what will come next for you?

JESSE: Yeah, it's awesome.

CDM: Have you thought at all about what will come next for you guys?

JESSE: For sure. But also I love that I'm not gonna be concrete about any of those things because I don't have to be. I think that's better for me. It's weird, in so many ways, knowing this whole album is about the end - internally, externally, the world, our contract. So much of it is just about the end. It's weird how I feel like I'm getting the best results that I've gotten because of that. I always pull from that place. It's so easy to pull from pain and negativity right now because it's all that's around us. And I'm thriving; our music is thriving, but it's gross. It's hard for me to deal with, because how does that happen? Why is that happening now? How much do they have to do with each other? The fact that I'm getting this much happiness within my little world, and everything else is the most fucked it's ever been. We're getting to do it right now and people are liking it a lot; I feel like I'm getting away with something that I'm not supposed to. But at the same time, every other moment that we've had informed this moment. I've always talked about certain things, like my feelings about social injustice, I've always put that into the songs. And maybe that's why we still get to have a voice right now. But yeah, it's hard for me to think about it too much because it just makes me go crazy.

CDM: When did you decide to start Therapy Records? How did the process with Danny come about?

JESSE: It naturally happened over time. Danny and I have been working with each other for the past six years - he's been my engineer for a while and then we brought him on for this album to produce it with us. This album felt like we finally found our process - we've been searching for it for a long time and we tried it with different people and stuff, but for this album, I was like, "We all think we know what we're doing. Let's just act like we know what we're doing and just do it without a producer coming in." Not that Danny didn't produce the record, but it was low pressure because it wasn't like we were hiring some guy and giving them half the album budget right off the bat to do that. It was freer for us to be like, "Cool, we get this great album budget, and we're going to do it all internally, ourselves. That's exciting, let's do it." Danny has been such a huge part of this process. I think the further we got into it, and the more we realised people want to be around us, I didn't want to start a label. Because, especially nowadays, every kid knows the ins and outs of the record industry. I feel like the whole new thing is nobody wants to get signed to a label. So with publishing, there's kind of more opportunity. I love giving people an opportunity for the first time, and publishing can be great for that. It doesn't have to be the biggest cheque in the world, or maybe for some people, it is a really big cheque. But you're not tied down to being anything other than a creative. If you got signed to publishing and you were in a band and then the band broke up, the publishing deal is still doing what it does, you can go do whatever you want and be solid in that world. It just seemed like less pressure, and more about giving people an opportunity that want to move to LA and are broke and don't have any money, but they really want to continue doing this and they're brilliant at making music but they just don't have the means to continue. I like giving people the opportunity to be able to do that. And, fuck the money part. Just putting people in a room together and writing a song. It's the coolest.

The Neighbourhood's album 'Chip Chrome & The Mono-Tones' is out now - listen to the album in full below: